In the United States, some people use the term curanderix as a gender neutral alternative for those who identify as neither male nor female. We can think of terms latinx and chicanx, which are widely used today for gender neutrality.

Education and training

There is the belief that curanderos are blessed with a God-given gift to help people heal and that such ability can be spotted from an early age. In Spanish, the word don is used to describe something like this. When someone is natrually talented in folk healing or some other activity it is said that the person has the don.

Another point of view is that the don is helpful but it is training, usually in the form of a long apprenticeship that ultimately leads to competency as a curandero. Training can be formal or informal. Some learn from their grandparent or aunt while some learn in school.

Training can also take place in the form of a college education. I have met people with accreditations to work in the health professions such as nurses, social workers and dieticians who integrate curanderismo into their work.

Curandera Jaysa Jones featured in this image, learned the healing traditions of curanderismo through an apprenticeship with a respected curandera from her community. In addition, Jaysa obtained a formal education from New Mexico State University in the field of social work. In this image, she raises an incense burner with smoke of copal during a community ceremony honoring the practices of Curanderismo.

Jaysa apprenticed with the late Doña Maclovia, an herbalist, consejera (advisor), and store owner in Albuquerque. Doña Maclovia managed a respected herb store known as yerberia in Spanish in the Barelas community.

Jaysa is a licensed clinical social worker in New Mexico who specializes in mental and behavioral health. She integrates Curanderismo with clinical social work to “provide a holistic approach to each individual” according to her.

Jaysa’s practice has focused on expanding access for the LGBTQ, Transgender, and non-binary communities to find care specially with issues like, anxiety, depression, and trauma known as susto in Spanish.

Apprenticeships have played a vital role in Curanderismo because healing practices have been traditionally passed down informally. This usually involves an elder member of the family teaching a younger one at home. However, that is not always the case, the traditions of Curanderismo can also be learned at community centers and schools.

For example, the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque hosts a yearly in-person class that serves as an introduction to Curanderismo. Students learn about history and theory but have the opportunity to participate in hands on lessons with practicing curanderos. Students are also able to make connections and find apprenticeships in Mexico. The name of the two-week long class is: Curanderismo Traditional Medicine without Borders.

Rita Navarrete (right) has been a regular presenter at this class for over a decade. She has been a practicig Curandera for over 28 years mostly in Mexico City and in a small village named Jilotepec. The village is located about 60 miles Northwest of Mexico City.

Jilotepec has a strong presence of Otomi people. They are an indigenous group of people with ancestral ties to Estado de Mexico. In her classes, Rita often references her Otomi ancestry.

Dr. Eliseo “Cheo” Torres is an innovator in the teaching of Curanderismo in the United States. Inspired by his childhood growing up in rural South Texas, he founded the Curanderismo class at the University of New Mexico in 2000. Dr. Torres subscribes to the notion that a student does not need to have the don to become a curandero. He believes that the skills can be taught and learned.

This class has been extremely succesful in bringing hundreds of curanderos, scholars, researchers and academics from around the world together in one forum. In addition, it has provided a respected academic setting in which Curanderismo can be studied. It is the only class of its kind in the United States with more than 2000 students having completed the class. Many of them anxiously await the return of the class every year to continue to learn and make connections.

Dr. Torres also teaches several online classes in conjunction with Dr. Mario Del Angel-Guevara, an assistant professor with the University of New Mexico. The courses are free and they are available on Coursera.

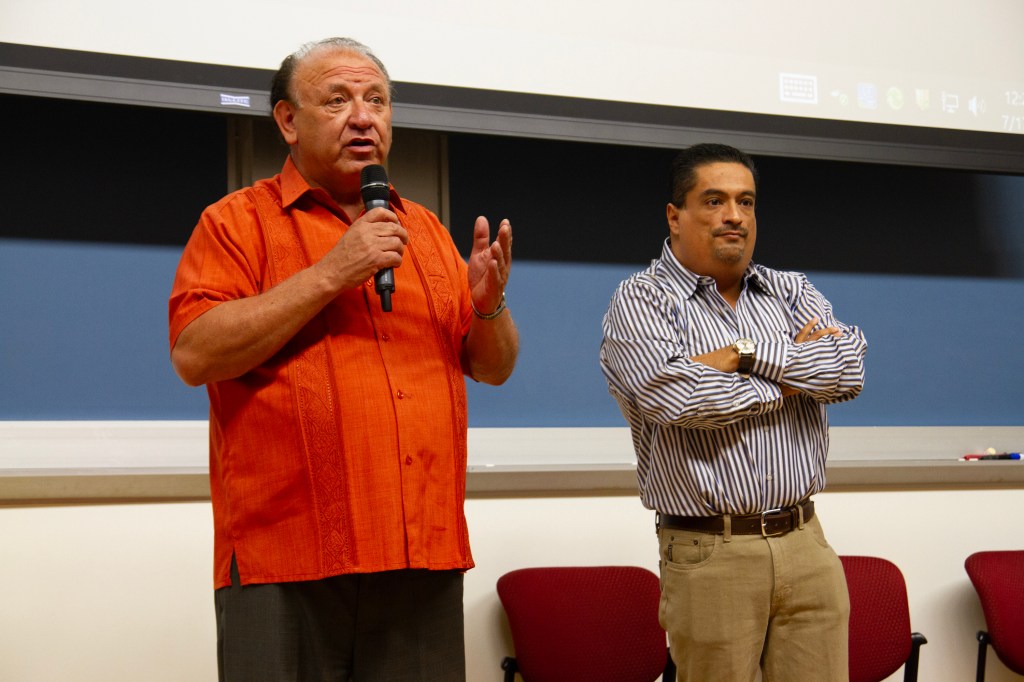

In this photograph, we see Dr. Eliseo “Cheo” Torres on the left and Dr. Anselmo Torres on the right.

Dr. Anselmo is a regular presenter at the class who focuses on the relationship between the Mexican holiday Day of the Dead and Curanderismo.

There is an institute in Cuernavaca, Mexico named Centro de Desarollo Humano hacia la Comunidad. It stands for Human Development Center for the Community and its abbreviation is CEDEHC. Their mission is to teach, promote and preserve the knowledge of what they call traditional natural health while creating a harmonious coexistence with people and nature.

They offer classes in traditional massage, Reiki, temazcal, and medicinal plants. They also teach classes about making shampoo and natural beauty products.

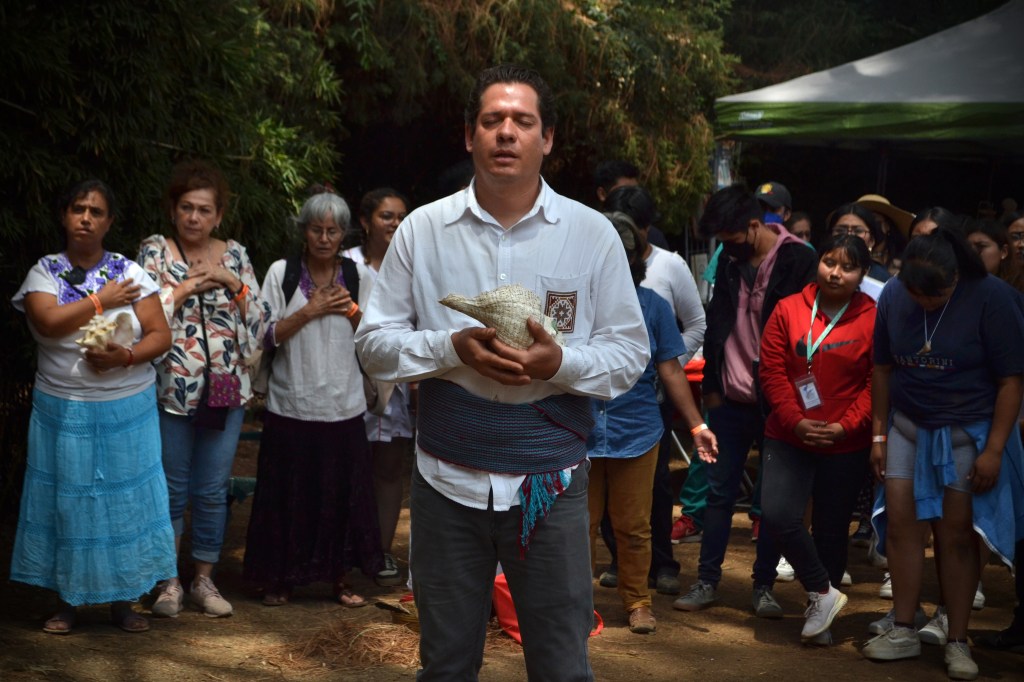

Juan Carlos Solano Alcocer, photographed here, has taught several classes at CEDEHC. In this image, he is leading the ceremony of the four directions, an important ritual for those connecting Curanderismo to its Mexihka roots.

He uses the sound of the conch shell, known as atecocolli in the Nahuatl language, as an offering to the direction of the East.

Mindset: Helping People

We briefly touched on the disctition between Curandero and Brujo in another section of this project. In my conversations with curanderos, those who see their work in the line of Curanderismo make the disctition that what they do is oriented towards healing only.

It is said that the intention to help people is one of the main prerequisites to become a curandero as opposed to a brujo. In what ways do Curanderos help people? One way is to empowering them to take control of their health. In other words, they encourage people to make lifestyle changes and to believe in their innate healing abilities. Curanderos often try to avoid creating a relationship of dependency between healer and patient.

Another way Curanderos help people is by charging very low fees for their services, working on asliding scale, or accept bartering. There have been many instances where Curanderos even offer their services free of charge. In other words, Curanderos believe that healing should be accessible to all regardless of socioeconomic status.

This is a portrait of Antoinette Gonzales, also known as Toñita an educator and practitioner of Curanderismo from Gonzales Ranch, New Mexico. In her teachings and practice, she encouraged people to empowering themselves by finding their innate healing abilities. Regardless of cultural affiliation, sexual orientation, or religion, she reminds people of their inner worth. She told me that “the holy” is within all of us not on the outside.

When identifying who is a true Curandero, Eliseo “Cheo” Torres in his book Healing with Herbs and Rituals reminds us that the amount of time spent healing is usually considered. He writes that in many cases a Curandero does not have another job, healing is the basis of his livelihood.

In this photograph, we see chiropractor Agustin Perez working on a treatment. In Mexico, such practitioners are often called “hueseros”, which is Spanish for bone setter. He has been working in this line of work for over 25 years.

When I visited his clinic or “consultorio” in Mexico City, I was surprised to find a waiting area with five people in line.

The clinic was located at his private residence that had been adapted as both a place of work and a home. People knew about him through word of mouth and referrals. There was no signage on the outside of the home advertising any services. There were about 3 rooms dedicated to therapy sessions. Agustin was working in 1 of the rooms and possibly his relatives were working in the other rooms. I got the impression that Curanderismo is Agustin’s livelihood.

In this healing practice he makes a neck adjustment related to chiropractic work. He also used mesotherapy and fire cupping.

In identifying who is a curandero there is also another important consideration. In the tradition of Curanderismo, curanderos rarely refer to themselves as such. Instead, they let the community which they serve make that determination. It is up to their clients, “pacientes”, friends, relatives, and colleagues to bestow the title of curandero to a person who they deem worthy of it.

This is a portrait of Dr. Danielle Lopez, a respected curandera from Pharr, Texas. The community of the Rio Grande Valley and San Antonio have bestowed that title on her because they see in her the “don”, the experience, the knowledge and the intuition that they expect of a Curandera.

Dr. Lopez has a long history as a practitioner and scholar of Curanderismo. Starting in her native community of Pharr she has taken plenty of house calls to serve her neighbors.

According to Pulse Magazine, a student-run magazine out of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Dr. Lopez has helped a diverse group of people, including a woman with a terminal form of cancer, a family facing deportation, and a young child suffering from fright or “susto” after a car accident.

This photo was taken at the Tepeyac in San Antonio, which is a tribute site to the apparitions of Lady of Guadalupe to Juan Diego at Tepeyac Hill in Mexico City. The Virgen of Guadalupe is of great importance to Curanderismo. The Virgen is the patroness of Mexico and a symbol of identity for many Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Her image has captivated the hearts of many Catholics too.

Leave a comment